Astronomy is the archetypal pure science. It can seem frankly pointless, especially when the projects like the Hubble Space Telescope cost a billion dollars or more. The point of astronomy is a vexed question, and one that politicians often have to engage with.

Some pundits justify astronomy on the grounds of the spinoffs, like better radio antenna technology. Some say our destiny is to emigrate from the planet, so we’d better start somewhere. Others simply assert unapologetically that peering into the heavens is what homo sapiens does, at any cost.

Here’s a different rationale. To my mind (as an ex astronomer) the deepest practical value of astronomy is it enables us to perform experiments that are just too grand to ever be done on earth. The limits of earth-bound experiments of course change over time, but during each era, astronomy has furnished answers to questions that elude terrestrial investigation.

For example, astronomers were the first to:

- measure the diameter of the earth (by observing the angle of the sun in the sky at noon at different latitudes, in ancient Greece and Egypt)

- measure the speed of light (by observing the transit of the moons of Jupiter)

- demonstrate the General Theory of Relativity (by observing the precession of the orbit of Mercury, and measuring during a solar eclipse the bending of star light by the Sun’s gravity)

- detect gravity waves (by observing the slowing of a binary millisecond pulsar).

And there must be other examples.

I mention General Relativity, which was another one of those apparently academic pursuits, until it came to the rescue a few years ago in the most practical way. Soon after the Global Positioning Satellite (GPS) system came online, its results started drifting. Engineers realised quickly that the high precision clocks in orbit were getting out of sync with those on the ground. And the explanation turned out to be gravity. According to General Relativity, a clock will run more slowly in a gravitational field, and because the force of gravity is slightly lower above the Earth than on the surface, the GPS clocks were running faster than expected. The effect was just a few parts in a billion, but enough to cause the positioning results to drift by a few metres, and whatsmore, to get worse over time. By reprogramming the GPS controllers to account for gravitational time dilation the problems were solved and the system has been stable ever since. So if it wasn’t for Einstein, your sat nav wouldn’t work, and you’d be lost. Or rather, more lost than you are now.

So astronomy is supremely practical. And here’s another thing. Astronomy occasionally provides the most profound and compelling truths about reality. My favorite example is a classic gooose-bump moment in the history of science: Galileo’s discovery of sunspots and his appreciation of what they meant. Until then, everyone thought the Sun was a perfect unchanging disc of light. After projecting the Sun through his newly uinvented teleschope onto a white sheet, Galileo soon noticed blemishes which rather put paid to the perfection. But much more importantly, Galileo saw that the spots were moving. They drifted across the face of the disc over a few hours, disappeared, and then returned, on the other side where they began. In today’s idiom, he might have said “O.M.F.G!” The sun turns out to be a turning ball! It was a critical moment of unification in human culture, contributing more evidence to the realisation that all of the things and all of the stuff in the universe are fundamentally the same. The Coppernican revolution was much more than star gazing: it reset humankind’s understanding of the mystical, reinforcing that everything is ordered, and ordinary. Corporeal, and explicable to human minds.

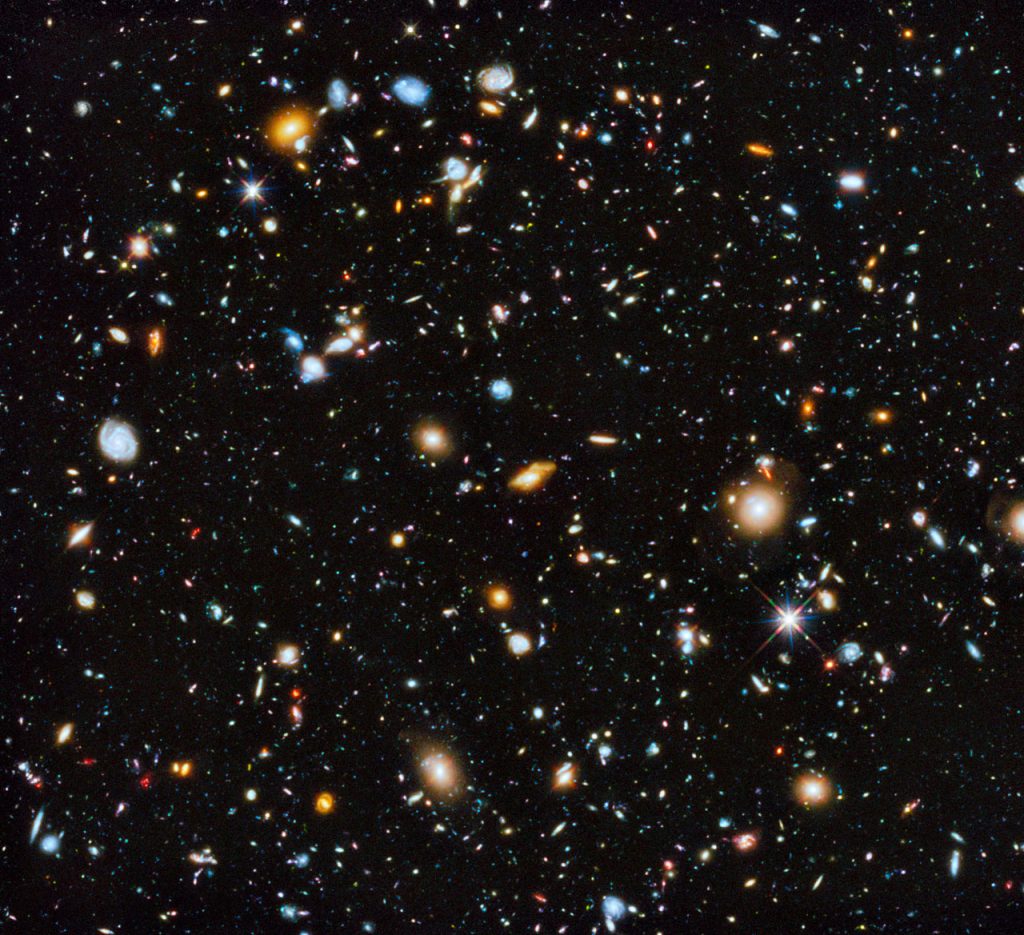

It’s not the only time a radical, instant, disruptive re-framing of our place in the world has been delivered by astronomy. It wasn’t really so long ago — in the early 20th century — that Edwin Hubble and his peers established that the ‘nebulae’ were actually galaxies just like the Milky Way, and that the universe therefore had to be tens of millions of times bigger than previously thought possible.

This kind of revelation about our place in the scheme of things only comes from astronomy.