Here’s a radical thought: why don’t we Internet engineers forget about identity?

Businesses and individuals identify each other in various ways and to different ends, but always basically in order to manage the risk of dealing with the wrong entity. By and large, we actually do identification pretty well. There are many mature analytical methods and standards by which identification can be analysed and designed, as just one element of risk management.

One of the difficulties in Federated Identity is that it too often pressures participants to change the way they do identification. Now there’s nothing wrong with change, and I’m not saying that identity management practices are perfect by any means. But they’re changing already. They always have and they always will. What I am saying is that global identification is never going to happen, and neither will global identification benchmarks, like Levels of Assurance. We can think globally all we like but risk management requires fundamentally that businesses will always act locally.

Identification practices undergo continuous improvement under circumstances peculiar to different businesses, industries and jurisdictions. Most industries at some level constantly monitor the adequacy of identification in the face of fraud trends, and make steady adjustments. Some identification protocols are legislated, as in the 100 point check of the Australian Financial Transaction Reports Act and anti-money laundering laws. Some protocols are set by industry overseers; for instance, doctor credentialing is regulated by local and state health agencies with a degree of national coordination. Ad hoc standards (more like habits really) emerge all the time, such as the way so many hotels have taken to photocopying driver licenses at check in. For the most part, identification rules are made up by industry bodies and by businesses themselves to suit their local risk profiles. In general there are no laws that prescribe how employers identify their staff, nor universities their students, nor professional bodies their members — just as there is no national identity card here.

In going online, several widespread problems in identification have arisen. We all know what the problems are: the inconvenience and cost of repeated registrations; the overhead of managing multiple accounts and often inconsistent authentication mechanisms (multiple passwords, and separately, the “token necklace”); the privacy risks that go with redundant registration information flows and records; identity fraud and “identity theft”. These problems are mostly separable and are amenable to improvement without imposing global identity management practices, let alone re-engineering identity itself.

The process of identification boils down to presenting certain pieces of claimed information about the person or entity, and validating those claims. In improving identification in the digital environment, we must focus with more precision on the real problems needing to be solved. And we must avoid wherever possible imposing changes from outside on the way that businesses choose to know their customers, members, staff, partners and users.

Around the world, governments and public-private partnerships continue to strive for big over-arching “Identity Frameworks”. I think we need to heed the lesson that Federated Identity is easier said than done. Really worthwhile efforts have repeatedly failed, none more significantly than Microsoft’s flagship identity solution Cardspace. I’m positive the underlying problem is simply that identity is not what it seems. Digital Identity is metaphorical; it’s not a real thing at all but instead is a proxy for a relationship. And we know that relationships are difficult to carry over across different contexts.

So what’s to be done? In my view, a subtle but significant course correction is due. Why don’t we drop down a level, forget about “identities”, and put our energies into making reliable information about claims more widely available? Fortunately, all the orthodox identity frameworks include Attribute Provision, and let’s remember that the Laws of Identity themselves teach that Digital Identities are “sets of claims made by one digital subject about itself or another digital subject”. I’ve discussed elsewhere that the interoperability of IdPs and RPs is more complicated than simply matching Assurance Levels, because it’s the details of the elemental claims that really matter. So why don’t we stop trying to centrally govern how identities are defined by Subjects and by Relying Parties, and focus instead on improving the mechanisms for conveying the more atomic claims that power those identities?

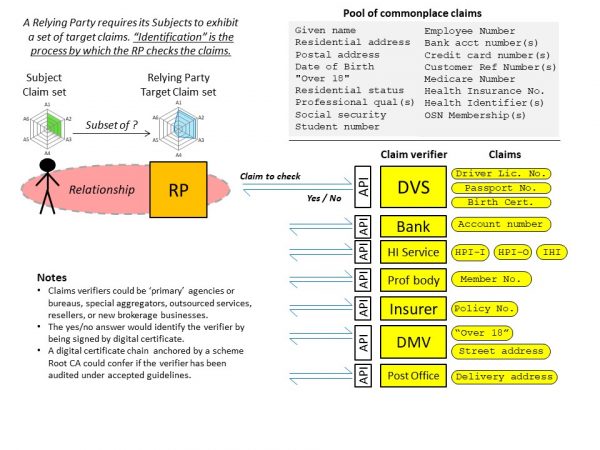

The diagram shows how a marketplace of verification services could grow around a set of commonplace claims.

NB: “DVS” stands for Document Verification Service, currently operated by the Australian Attorney Generals Department, which allows state & federal government agencies here to inquire as to the validity and currency of a range of identity documents.

The approach includes many of the standard privacy and security features of higher order Federated Identity systems, such as information hiding APIs delivering only ‘yes’/’no’ answers to claims queries. But the approach stops short of describing any “identities” per se or characterising “assurance levels” and the like, leaving Relying Parties to continue to set their own identification rules, and to realise those rules by shopping around for claims verifiers that suit their purposes.

To help RPs make up their own minds about the veracity of each attribute in this marketplace, the Yes/No answers from each Claim Verifier (aka Attrinute Authority) would be digitally signed by the verifier. The certificates used to validate the signatures would chain into a root CA for the whole scheme; every verifier in the scheme would be certified and regulalry audited, with their status reflected in their certificate. This sort of PKI means that the signed Yes/No answers can be seen to have originated from legitimate organisations, andorsed by the scheme. That is, there is clear provenance of the claims, the organisations that issued them, and the manner in which the claims were conveyed to the RP.

The Yes/No answers could be delivered on demand, in real time, or (as is my preference) the answers could be baked into end user certificates issued to convenient personal devices like phones or smartcards, and then presented directly by the user, for better privacy and control.

The suggested system has the following qualities:

-

- It does not impose any identification protocols on businesses, who remain free to select which claims and combinations of claims they want Subjects to exhibit.

-

- It does not change the context in which businesses deal with their customers/members/staff/partners/users.

-

- It is contestable. While there will be natural authorities (or ‘sources of truth’) for many claims like driver license numbers or date of birth, the proposal allows for other organisations to offer claims validation. Secondary data sets can be just as reliable (or even more so) for claims such as street address, alternate names etc. Information brokers can be expected to value-add certain claims, attest to baskets of claims, and/or bundle claims validation with other business services.

-

- It is much easier to ascribe liability around the validation of precise claims than the validation of “identity”; this approach should be more palatable to banks, government agencies and so on than other Federated Identity concepts where IdPs are asked to underwrite ‘who someone is’.

-

- It is pragmatic; it avoids semantic technicalities like the difference between “authentication” and “authorization”; the proposal simply provides uniform market-based mechanisms for parties to assert and test elemental claims as a precursor to doing business.

In closing, I’d like to quote Dazza Greenwood on identity:

“Former Speaker of the House Tip O’Neil used to say that all politics is local. Similarly, it can be said that all identity is local as well. Not necessarily geographically local. A parent can have children across the country and a bank for example can have account holders all over the globe. But they are “logically local” in the sense that they are all “home grown” and make sense largely only in their internal context. The account number by which each banking user is primarily known and the attributes surrounding that number are not similar to the naming and identity scheme required by medical clinical systems, for example. One size does not fit all because the subtle contours and content of identity is not monolithic.” Ref: Authentication and Identity Management: Information Age Policy Considerations, Greenwood, 2003.

Indeed: identity is not monolithic. We might make much better progress on the digital identity challenges if we dropped down a level and tried dealing with identity’s common parts instead.