Infostructure patterns

One of the hottest topics in the digital economy has for some time been data sharing. Many proposals are evolving in Open Banking and Open Data, alongside digital identity frameworks and more specific digital credentialling. I’m seeing verifiable credentials methods and thinking leaning towards verified data.

“Infostructure” is a term for the orchestrated systems of policies, standards, rules, technologies and architecture that help control the use of important information.

Strikingly similar patterns are evident in the infostructures that have emerged in digital identity, open banking, card payments and digital credentialing. These patterns can help us solve the scaling problems that held back acceptance of digital IDs, and streamline the way we architect a number of important programs. It turns out that many of these programs are variations on a common theme.

The Standard Model of Digital Identity

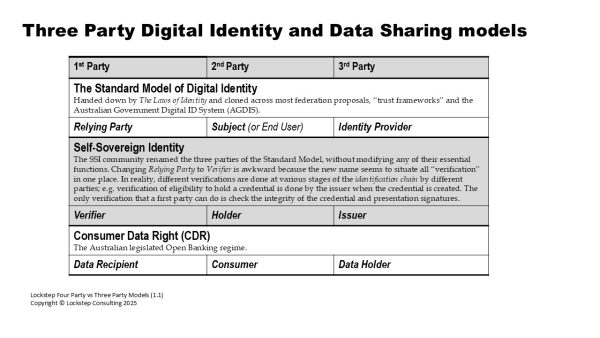

The digital identity field has been dominated for twenty years by a supply-and-demand model featuring three types of participant: Subjects, Identity Providers (IdPs) and Relying Parties (RPs).

Technical standards, government policy, industry associations, businesses, and legislation have all been structured around this Three-Party model in which digital identities are “issued”, “held”, “presented”, “exchanged”, “used” and/or “consumed” as if these are a type of good.

The Standard Model has not gone well but we can look to a much older canonical data sharing model for help.

What’s holding back the digital identity market?

One huge historical challenge has been apportioning liability and allocating reasonable fees for digital identity services. It’s never been really a clear in the standard three-party model of Digital Identity which parties gain the most economic benefit from assured qualities of the data they consume, and how do fees get fairly levied for these assurances.

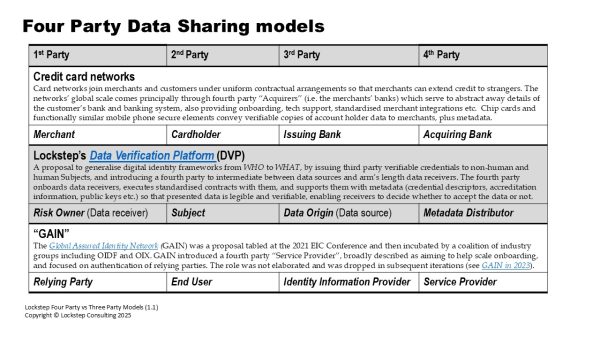

This problem was solved over sixty years ago with the network business model of the credit card schemes. They realise a two-sided market of payment card issuers and merchants. These are just special cases of ID Issuers and Relying Parties.

Credit card networks have one core job: distribute and verify customer IDs so that merchants can extend credit to customers without needing to know them, and moreover, without knowing the customers’ banks either. That is, the networks join the credit providers (customers’ banks) to merchants without the merchants needing to make their own bilateral arrangements.

Don’t make this personal!

Another problem with traditional approaches to digital identity is they tend to over-complicate the problem, by framing it in terms of solving for “who someone is”.

Personal identity is complicated, hard to define, and impossible to standardise. In real life, “identity” means different things to different people. In transactional settings (where digital identity matters) each party needs to know different things about their counterparties, so a singular answer to “who you are” is fundamentally elusive.

On the other hand, if we reframe the digital identification problem around as What Do You Need To Know about a counterparty, and if we expect to address that question in different ways according to context, then the possible solutions look rather different from the traditional three-party model.

That is, let’s recognise digital identity as a special case of verified data sharing — and keep the personal out of it.

Generalising from Three Parties to Four

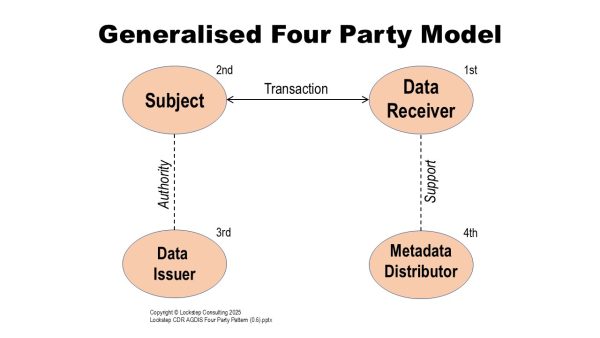

Lockstep has been working on a four-party data verification platform (DVP) architecture inspired by the credit card network model. The DVP augments the traditional three players with a new fourth party that intermediates between Relying Parties and Issuers.

As I look at it, the awkward failures of Federated Identity (despite it seeming like such a great idea) shows that digital identity is not what we thought it was. But the tools and infrastructure that we’ve developed along the way can be repurposed.

It will be far more useful (and far less complicated) if we generalise digital identity frameworks from WHO to WHAT.

We should be issuing third party verifiable credentials to non-human Subjects (IoT devices, virtual agents, even AI algorithms themselves) to prove all the qualities and properties of interest. And to make these assertions legible and acceptable at scale, we need a new type of fourth party to intermediate between data sources and data receivers when these are at arm’s length from each other.

The fourth party onboards data receivers (just like acquiring banks onboard merchants into the card systems), executes a standard form of contract with them, and supports them with metadata (credential descriptors, accreditation information, public keys etc.).

The fourth party is the missing link in scalable systems of verifiable credentials.

Verifiable credentials cannot verify themselves. That is, the verification step requires essential metadata which need to be distributed to relying parties. This metadata includes the public keys needed to cryptographically confirm the signatures on credentials and presentations. It also includes the names and target values of such things as credential issuers, credential types, accreditations etc. These are the critical details needed for relying party software to make programmatic decisions to accept or reject the data that it’s being presented with.

Comparing Three Party and Four Party models

The following tables compare several paragons of the two types of model.